By Mr. Tom: Changing Sleep Patterns of a Toddler

Abstract

Sleep problems in children can be very common. Sleep problems can be refusal to go to sleep, getting up in the middle of the night, or wanting to sleep in their parent’s bed. Piazza, & Fisher (1991) reported that one study found that between “20% to 30% of children between 1 and 4 years of age (Lozoff, Wolf, and Davis (1985)” (p. 129); have some sort of sleep issue. Kataria, Swanson, and Trevathan (1987) reported that 84% of children with sleep problems continued to have them at 3-year follow-ups (Piazza, & Fisher, 1991). Another study by Quine (1991) showed that 50%-75% of children with sleep disorders continue to have them at 3-year follow-ups (Durand, Christodulu, 2004).

These sleep problems can cause other more serious problems. According to Ortiz & McCormick (2007); when the child does not get enough sleep, they can seem to have “paradoxical hyperactivity (Kuhn, Mayfield, & Kuhn, 1999), which, in combination with poor impulse control in the classroom, may lead to a child being misdiagnosed as hyperactive (Bergman, 1976).” (p. 512)

According to Ortiz & McCormick (2007), this lack of sleep could also lead to “anxiety, depression, and substance abuse disorders (Mindell, Kuhn, Lewin, Meltzer, & Sadeh, 2006)” (p. 512) Durand, Christodulu (2004) found

Brylewski and Wiggs (1999) investigated the relationship between sleep disorders and daytime behavior problems and found that individuals with sleep disorders scored significantly higher on the Irritability, Stereotypy, and Hyperactivity subscales of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC; Aman, Singh, Stewart, & Field, 1985). Similarly, Wiggs and Stores (1996) found that children with sleep disorders had higher scores on all subscales of the ABC except Inappropriate Speech (p. 83)

In a paper titled Behavioral Parent-Training Approaches for the Treatment of Bedtime Noncompliance in Young Children by Camilo Ortiz & Lauren McCormick, they state that there are several different approaches to treating bedtime refusal. These approaches are extinction, graduated extinction, bedtime pass, positive routines, fading/response cost, parental presence, and social story.

Extinction is when you ignore the child and let them cry and tantrum until they fall asleep. This can be tough on the parents, especially the first night because of an extinction burst but usually helps the children go to sleep after about three days. Graduated extinction and positive routines were developed to help the parents not be as stressed about the extinction intervention.

Graduated extinction is when on the first night, the parent checks on their child after 5 minutes and then 10 minutes, followed by 15 minutes until the child falls asleep. The second night the same procedure starts again, but the first check will be at 10 minutes.

Another slight change to this is giving the child a bedtime pass. One time per night, they are allowed to leave their room. Parents and children seem to like this approach.

Positive routines help get the children into a pre-bedtime routine by having them do several things the child likes. Once one is completed, the child is praised, and the next one starts. This procedure does not start until the child appears to be tired. The bedtime should be gradually faded back to when the parents want the child to go to bed. This avoids extinction bursts, so parents are more likely to continue treatment. Once the child wakes up the next day, they should be praised.

Fading/response cost: The child’s bedtime is moved back to when the child is sleepy and then gradually faded to the appropriate bedtime. They are also woken up at a scheduled time each morning. If the child does not fall asleep within 15 minutes, the bedtime the next night is moved back 30 minutes. Response cost can be added if the child is not asleep within 15 minutes. The response cost would be to remove the child from the bedroom for 1 hour. They can play with whatever they want but are not allowed to sleep. After 1 hour, they go back to bed. This reduces struggling with the parents but causes the parents to potentially stay up later themselves.

Parental presence is based on the theory that the child has separation anxiety. The parent would sleep in the child’s bedroom for one week to show that the parents would still be there in the morning.

Social Story with a rewards program is when the parents read a social story about going to bed and then leave a reward under the child’s pillow if they went to sleep without any problems.

For this study, I will focus on bedtime noncompliance: which Ortiz & McCormick, (2007); described as “stalling, whining or tantruming when bedtime approaches” (p. 511).

Subject

The subject of this study is a 3-year-old boy named Joe. He refuses to go to bed before 10 pm and will wake up by 7:15 in the morning without taking a nap during the day. By the end of the day and periodically throughout the day, he will get overtired. When he gets overtired, he will hit, yell, throw things, and be very non-cooperative. This overtired behavior is very different from his normal happy behavior. Joe has gotten into the habit of falling asleep on the sofa while watching a movie, which might make it harder to have him fall asleep in his bed (Kincaid, & Weisberg, 1978).

Method

I will use a combination of positive routines, fading/response cost, and a rewards program. The rewards program, in combination with positive routines, was chosen because Joe responds well to any type of reward for good behavior we give him. The only time rewards do not seem to work is when he is overtired. Blampied, & France, (1993); described positive routines as “structured pre-bedtime activities and fading bedtime to earlier and earlier times” (p. 484). The child will be allowed to go to sleep when he naturally wants to determined by the baseline data. Once the chain is established, the bedtimes will gradually be moved up to the pre-established bedtimes (Adams, & Rickert, 1989).

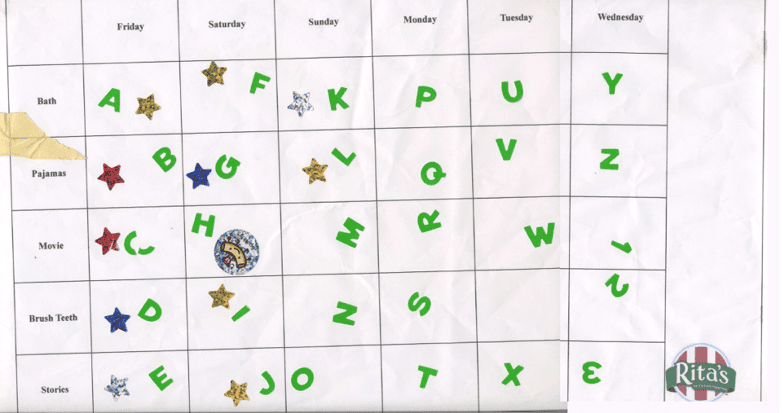

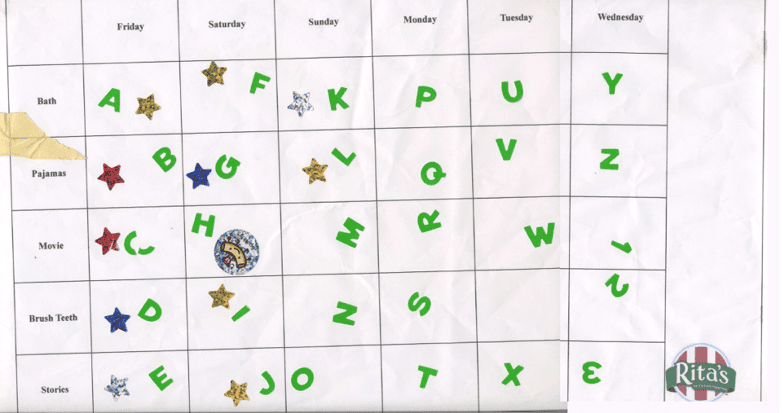

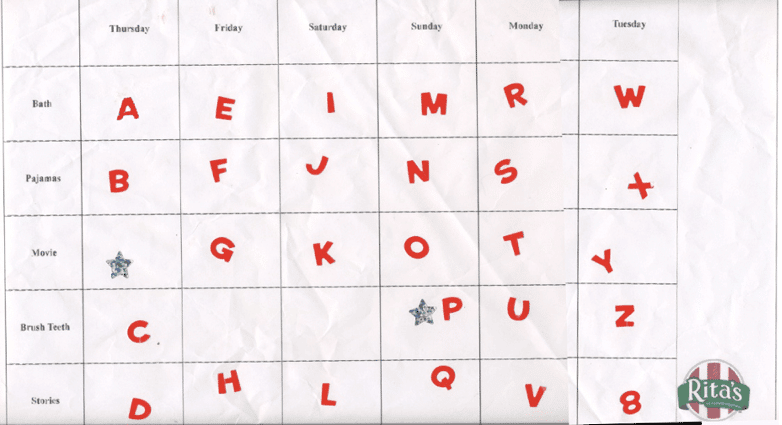

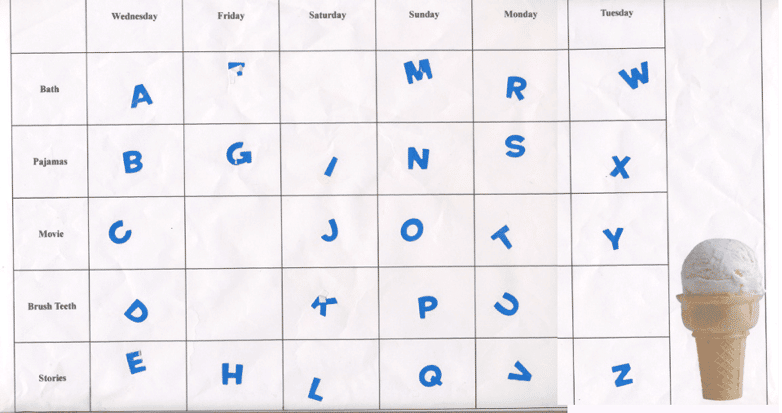

The nighttime routines we chose for Joe are taking a bath, putting on pajamas, watching a movie to relax, brushing teeth, and listening to stories. After each activity that Joe follows directions, he will be praised and will earn an alphabet letter sticker. He can then put the sticker letter on the board under the day of the week and the activity he earned it for (see chart). At the end of the week, he hopefully will have collected the entire alphabet, and I will treat him to Rita’s Water Ice. He will be able to earn five stickers a day, so by the end of the week, he should have earned his water ice. A study found that earning the tokens worked well, but the response cost of losing one over time appeared to work better. The only question is that the response cost also had feedback as to why they lost the token, so the feedback might have been just as important. In this study, the children either started with 15 tokens and lost tokens for bad behaviors or started with 0 tokens and earned them. At the end of the session, if they had 12 tokens, they would get candy (Conyers, Miltenberger, Maki, Barenz, Jurgens, Sailer, Haugen, & Kopp, 2004). The goal is to have Joe pick out the next letter in the alphabet instead of losing a letter because he will respond better to earning it than losing it. I chose to use letters because of an article titled Alphabet Letters as Tokens by Kincade. In it, they used letters to help the students recognize and label the letters even though the students were not specifically trained on the letters (Kincaid, & Weisberg, 1978).

The goal of these routines will help train him to get ready to go to sleep. Positive routines continue by placing the child in bed and being told to go to sleep once the routines are completed. According to Adams, & Rickert, (1989); if the child gets out of bed, the parents would place them back into bed and say, “The routine is over; it is time for bed!” (p. 758).

I have tried to tell Joe to go back to bed, and he fights and refuses to go to bed. Ignoring doesn’t help, and he will even go right back downstairs to watch more TV. For this reason, I am going to use a faded bedtime/response cost to get him to stay in bed. When I put Joe to sleep for the start of the intervention, it will be 30 minutes after his average natural time he falls asleep. Joe will not be able to sleep until then. If he is not asleep within 15 minutes, his bedtime will be moved back 30 minutes the following night. If he fell right to sleep, his bedtime would be moved up 30 minutes the following night. On the nights that Joe does not fall asleep within 15 minutes, he will be made to get out of bed and stay up for 30 minutes. During that time, he can do whatever he wants, except sleep. This removal from his bed would be the response cost. The goal of the response cost is so that Joe only associates his bed with sleeping (Piazza, & Fisher, 1991; Ashbaugh, & Peck, 1998). An alarm will be set the next morning to ensure he gets up on time, and he will be praised for going to sleep.

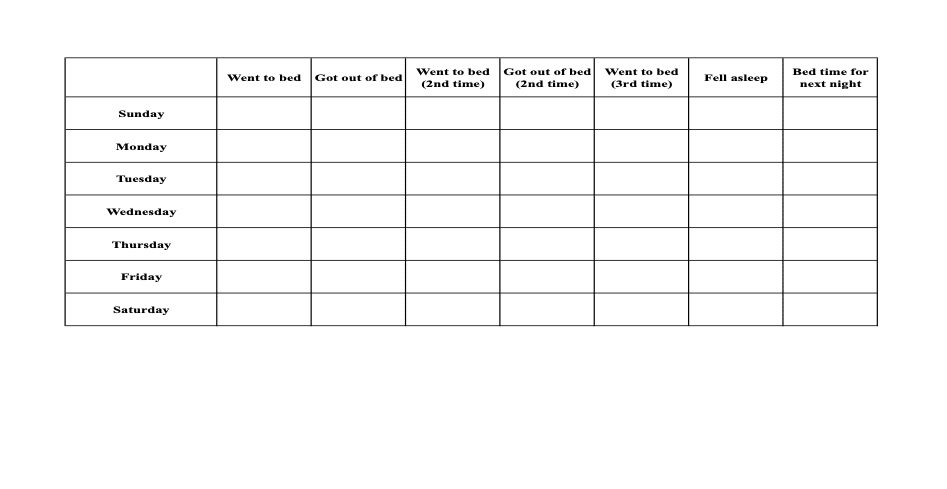

Baseline Data

Joe was allowed to fall asleep whenever he naturally wanted to for this week. This was done so I could find the average time that he naturally wants to fall asleep. He fell asleep between 9:00 and 10:45, which is a significant time difference. Since the average time, he naturally wants to fall asleep is 10:05 moving his bedtime back to 10:35 should not be a problem. 10:25 or 10:30 is when Joe fell asleep on 3 of the 7 nights.

| Thursday | Friday | Saturday | Sunday | Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Average |

| 10:25 | 9:00 | 10:25 | 10:30 | 9:55 | 10:45 | 9:40 | 10:05 |

Results

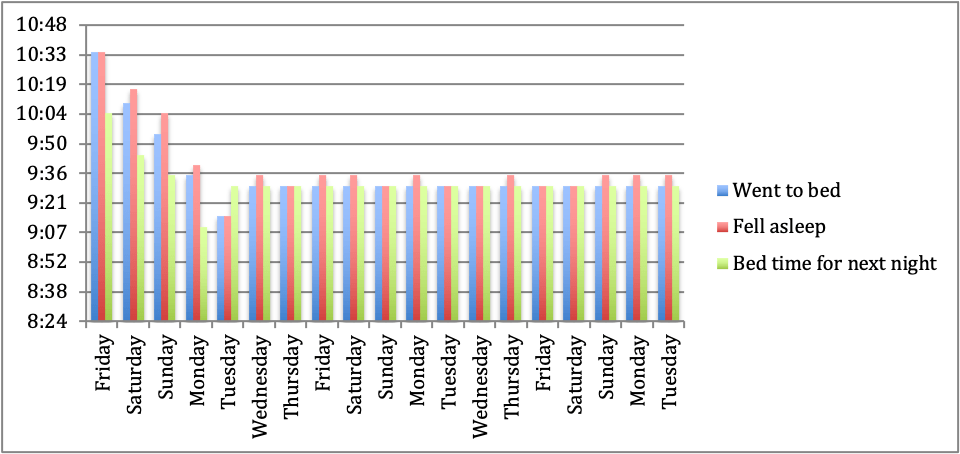

Joe did remarkable well with his program. The program’s goal was to get Joe to bed by 9 pm. By the fifth night, Joe went to bed at 9:15. After he had gone to bed that night, we decided that 9:30 was a better time for Joe to go to bed. We wanted to spend the extra 30 minutes with him at night, and Joe also asked why he had to go to bed so early.

We did our best to keep him following the fading/response cost part of going to bed 30 minutes before or after the night before, but some nights we were off a couple of minutes. The first night Joe fell asleep at 10:35 and stayed in bed for the night. The next night he was asleep by 10:15. The following night, he stayed up for almost 15 minutes and didn’t fall asleep until 10:05. The fourth night, Joe fell asleep at 9:40 and 9:15 on the fifth night. This was the night we changed his new bedtime to 9:30. After this, Joe went to bed at 9:30 every night and did not have any problems falling asleep. Throughout the three-week period, Joe never got out of bed or stayed up more than 15 minutes.

The alphabet sticker chart was also a great success. Joe was very excited about it and loved earning his letter stickers. After he earned his first Rita’s, he hung up his chart in his room over his bed. We have also seen Joe developed a new interest in letters while not working on his chart. In the past, he had only been interested in the first letter in his name and identifying his written name. Joe was so proud of his letter chart that he would show it to anyone who would come to the house, including the plumber.

For the first week, Joe did remarkably well. On the fifth night, he did not earn his sticker for brushing his teeth. This was the only sticker he missed. In the second week, he refused to brush his teeth on the second and third days. Since brushing his teeth was Joe’s only problem, we took Joe to the store to buy a new toothbrush. While picking out a new toothbrush, he wanted to try kids’ mouthwash. The mouthwash was a very important motivator for Joe. He brushed his teeth every night for the rest of the week and earned his second trip to Rita’s water ice. By the third week, Joe wanted to earn ice cream, so we changed his reward. Joe didn’t have any problems on the first day. We took Joe to a fair on the second day, and Joe fell asleep in the car before we could do any of his positive routines. Joe’s schedule was messed up the next day, and it caused serious problems with his chart, but he still fell asleep right around 9:30. Joe took his bath in the afternoon and was allowed to put on his pajamas before dinner. Since he didn’t fight us, we gave him his stickers for taking a bath and putting on pajamas even though it was before his bedtime routine started. Once we tried to start his routine for the night, Joe fought us at movies and brushing his teeth but not for stories. The next day Joe fought us about taking a bath and did not earn his sticker. After he did not earn this sticker, he seemed to realize that he had to follow the rules or he wouldn’t earn his reward. He had no more problems until the final night while brushing his teeth.

First Weeks Chart

Second Weeks Chart

Third Weeks Chart

Conclusion

The program was a great success. Joe no longer gets overtired, so most of his overtired behaviors are gone. It is great to have a happy boy again who is going to bed at an appropriate hour. The program’s final week has shown us that he still needs the program, but I feel it can gradually fade. I’m not sure that earning stickers for pajamas and stories means much to Joe at this point. I will combine them with bath and brushing teeth and give Joe 4 extra days to earn his letters. This way, every aspect of his routine is still being included, but he can still earn the entire alphabet.

References

Adams, L. A., & Rickert, V. I. (1989). Reducing bedtime tantrums: Comparison between

positive routines and graduated extinction. Pediatrics, 84, 756-761.

Ashbaugh, R., & Peck, S. M. (1998). Treatment of sleep problems in a toddler:

A replication of the faded bedtime with response cost protocol. Journal of Applied

Behavior Analysis, 31, 127-129.

Blampied, N. M., & France, K. G. (1993). A behavioral model of infant sleep disturbance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 26, 477-492. Conyers, C., & Miltenberger, R., & Maki, A., & Barenz, R., Jurgens, M., Sailer, A.,

Haugen, M., & Kopp, B., (2004). A comparison of response cost and differential

reinforcement of other behavior to reduce disruptive behavior in a preschool classroom.

Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 37, 411-415.

Durand V. M., Christodulu, V. K., (2004). Description of a Sleep-Restriction Program to Reduce

Bedtime Disturbances and Night Waking. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions,

Volume 6, Number 2, 83–91.

Kincaid, M. S., & Weisberg, P. (1978). Alphabet letters as tokens: Training preschool children in

letter recognition and labeling during a token exchange period. Journal of Applied

Behavior Analysis, 11, 199. Ortiz, C., & McCormick, L., (2007). Behavioral Parent-Training Approaches for the Treatment

of Bedtime Noncompliance in Young Children. JEIBI, 4 (2) 511-525.

Piazza, C. C., & Fisher, W. (1991). A faded bedtime with response cost protocol for treatment of

multiple sleep problems in children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 24, 129-140.